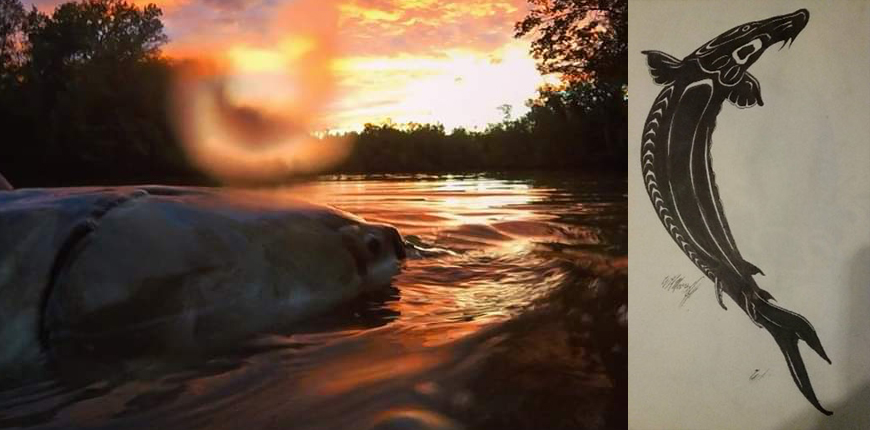

Photo by Pamunkey Tribal Member, Desiree Nuckols | Sturgeon drawing by Pamunkey Indian Tribe member, Kirk Moore

Sturgeon Species Recovery Grant

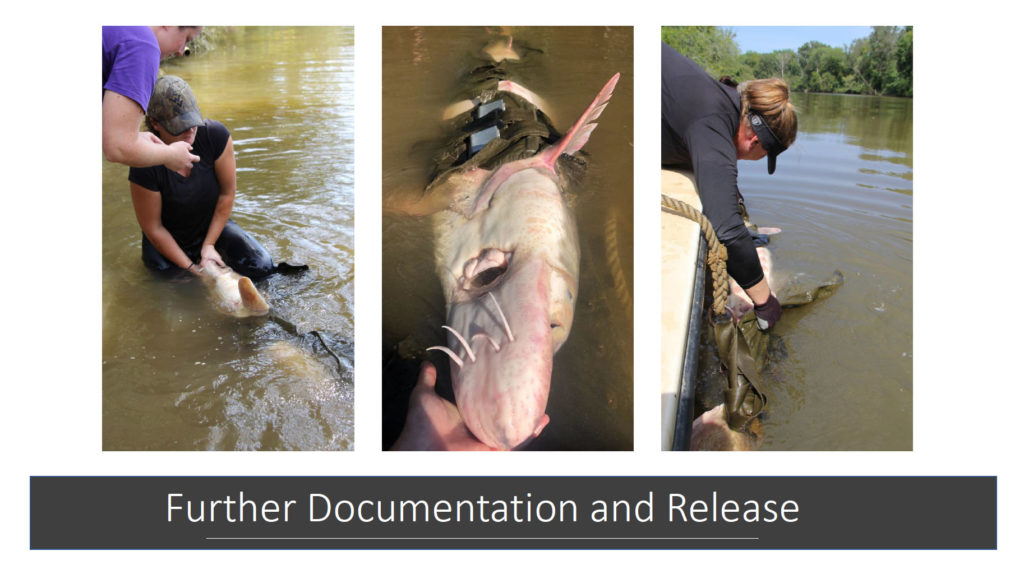

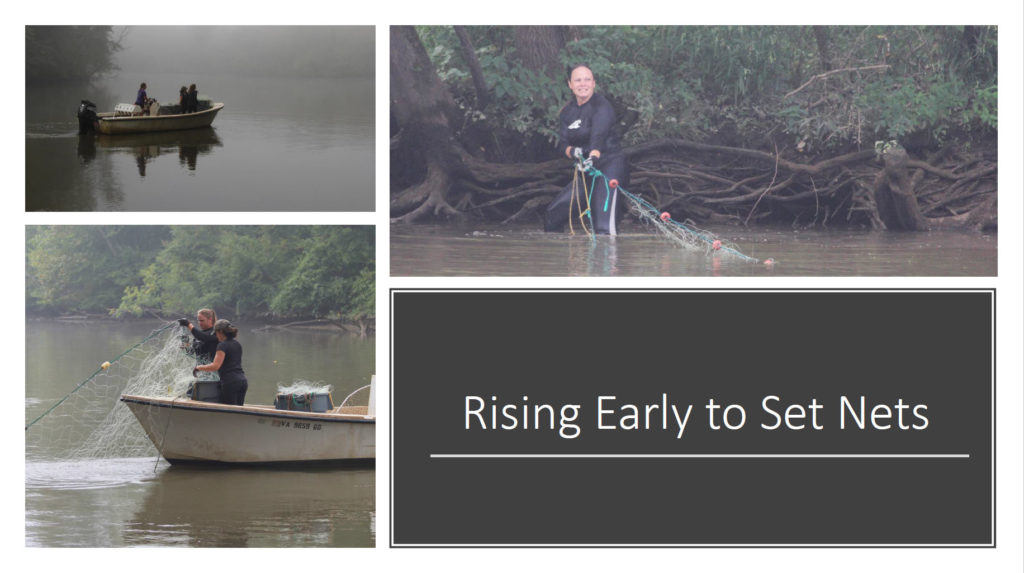

The Pamunkey Indian Tribe, in collaboration with Chesapeake Scientific, LLC consultant Christian Hager, will assess the current number of Atlantic Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus) spawning populations and the abundance of fish within those populations to expand the ecological knowledge and stewardship of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi Rivers under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) grant funding. In February 2012, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) listed the Atlantic Sturgeon in this distinct population segment as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA; 77 Federal Register 5714, 5880). A small population of sturgeon was found living in the Pamunkey River in 2013 (Kahn, Hager, Watterson, Russo, Moore & Hartman, 2014). The duration of this project is July 2018 – November 2020. Click the link below to access the Pamunkey Indian Tribe Sturgeon Grant.

Four interconnected goals addressed in the grant include:

- Create a more comprehensive ecological picture of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi Rivers and develop a Pamunkey River Keeper role to continue the work and foster improved stewardship.

- Improve physical models of the rivers to better understand the relationship of water quality factors to Atlantic Sturgeon spawning habitats.

- Calculate the spawning populations in the rivers.

- Determine the validity of off-the-shelf side scan sonar for enumerating sturgeon.

The Atlantic Sturgeon

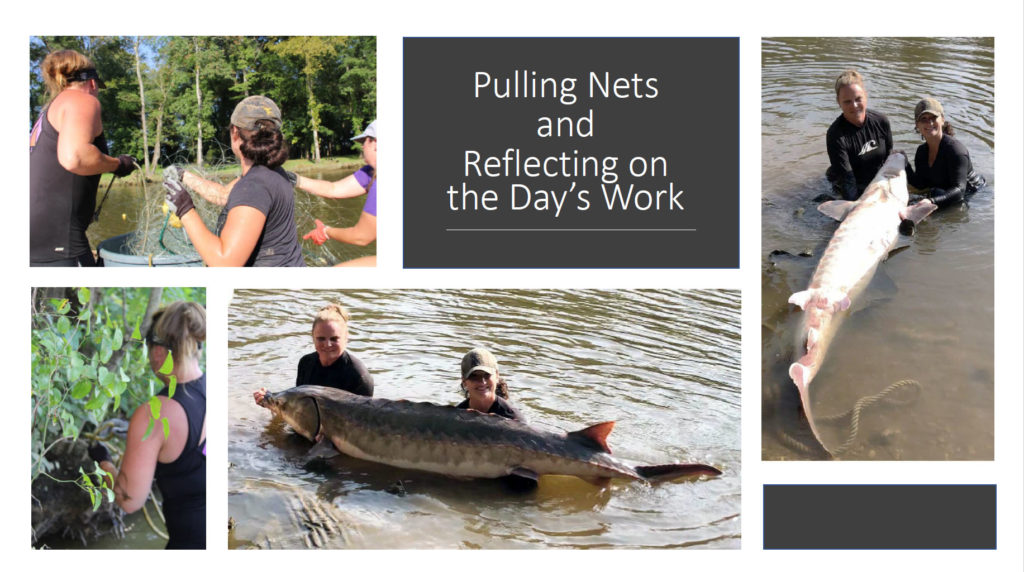

Atlantic Sturgeon have a prehistoric-like appearance with their five rows of bony plates or scutes, elongated snout, shark-like tails, four well-developed barbels, and absence of typical scales. This family of fish (Acipenseridae) swam with the dinosaurs around 120 million years ago. Adult sturgeon can reach lengths of 14 feet and weigh up to 800 pounds, however, sturgeon in this distinct population range may reach 5 feet and 90 pounds (male) to 8 feet and 225 pounds (female). As bottom feeders, they have a protruding vacuum-like mouth on the underside of their head for eating aquatic insects, shrimps, mollusks and some fishes living in the substrate. They mature slowly (males in just under 10 years and females in around 10 years) and are long-lived (males about 30 years and females about 60 years). Sturgeon are anadromous fish, meaning they spend most of their lives in saltwater and migrate upriver to spawn in freshwater. Females reproduce only once every 2 to 6 years, favoring a gravel or clay chunk bottom to which their eggs (up to 2 million) can cling. DNA samples and tracking records provide that these fish return to their natal rivers to spawn.

Overfishing and habitat degradation are primary causes for the decline in the sturgeon population. During the 18th and 19th century the Chesapeake Bay supported the second greatest caviar fishery in the United States, however, by the end of the 19th century the overharvesting of sturgeon for their roe and flesh had severely depleted the population. The 1890 peak Atlantic coast catch of 7,382,000 pounds had dwindled to less than 100,000 pounds by the 1920s. Virginia’s ban on harvesting of sturgeon less than four feet in length in 1925 did little to spark the species’ recovery, requiring the state to issue a moratorium on the harvest of sturgeon in salt or freshwater in 1974. Today, there are additional challenges to the species’ recovery beyond fishing and bycatch. Increased deforestation of land (e.g., agriculture) and development (e.g., industry, housing) results in erosion and deposits of sediment and toxins in the rivers, blocking sunlight needed by underwater grasses and small fishes. Settling sediment smothers shellfish and other bottom-dwelling species and covers the gravel-like river bottom favored by sturgeon for spawning. Agricultural fertilizer and wastewater seeping into the river increase the amount of nutrients (e.g., nitrogen and phosphate) in the water leading to eutrophication, a process in which nutrients promote algal bloom that blocks sunlight and leads to oxygen depletion as plants die and bacteria consume the remaining oxygen. Sturgeon are sensitive to dissolved oxygen levels and water temperature (for spawning). In addition to the habitat degradation, the late maturation of females and the lengthy interval between spawning cycles further complicate recovery efforts.

Sturgeon and the Pamunkey Indian Culture

The sturgeon species played an important role in Pamunkey Indian culture as food, source of income, and coming of age ritual for young men. Fisheries along the East Coast processed sturgeon meat, eggs, and oils for export to Europe. The roe was considered a delicacy and the most favored and highly valuable part of the sturgeon. The Pamunkey used a variety of fishing methods to catch sturgeon.

While archaeological studies provide that the Pamunkey diet included sturgeon, the fish also served as a source of income. From the 1800s through the early 1900s, the Pamunkey and other fishermen along the East Coast took advantage of the market demand for sturgeon. Lester Manor, a small town that used to be located right outside the Pamunkey Indian Reservation, played an essential role in the processing and transport of fish. The town was often referred to as “Fish Hall” (or “Fish Haul”) due to the high volume of freshwater fish being processed and transported along the rail that cut through it. Built in 1859, the Richmond and York River rail line once operated an established depot at Lestor Manor which supported transport of fish, including sturgeon and its roe, to the Baltimore commission houses. The high demand for sturgeon meat and roe was the main contributor to the rapid decline of these prehistoric fish along the East Coast.

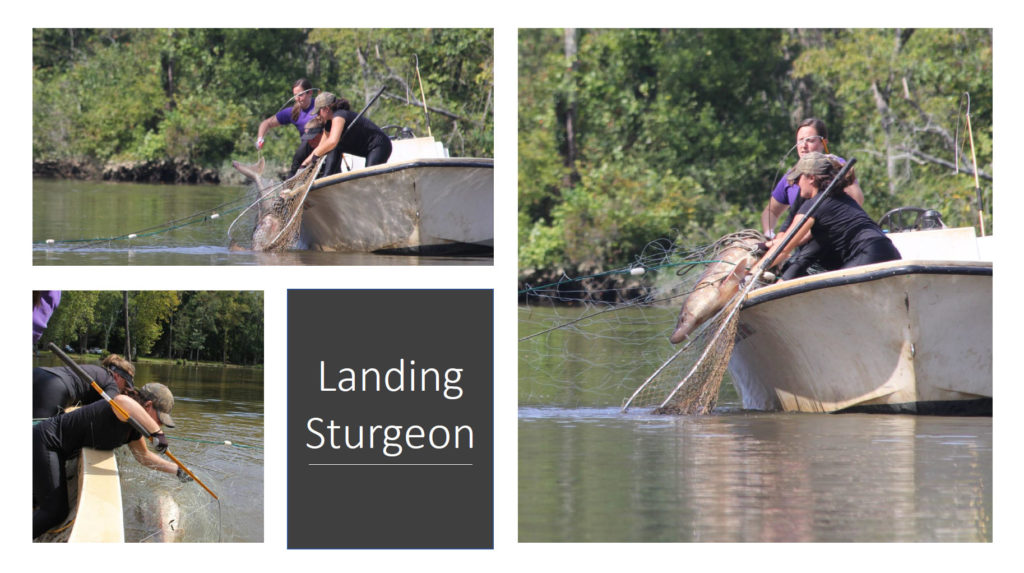

The Pamunkey people utilized various approaches to catch sturgeon. A widely used commercial approach to harvesting fish involved the use of drift nets (or seines) that hang vertically in the water with floats attached to the top of the net and weights attached to the bottom. Fishermen know that a sturgeon is entrapped in the net when the floats pull down closer to the water’s top. The more traditional Pamunkey method is the construction of a bush-fence to trap or contain fish as the tide lowers. During low tide, poles (usually wooden) were driven several feet apart into the mud at the entrance to creeks feeding into the Pamunkey River. Pliable branches or marsh grass were used to weave a fence with the top sloped upstream so that fish could pass over the fence during high tide. Once the tide rose and fish swam into the creek, the brush hedge would trap the fish in the creek as the tide receded. Pamunkey fishermen retrieved the entrapped sturgeon using a constructed jig-hook.

Based on interviews with the Pamunkey elders, the capture of an Atlantic Sturgeon played a role in the right of passage ritual for young Pamunkey men. The young men would catch and ride a sturgeon a certain distance to earn their way to adulthood. At completion, the Pamunkey boy would then become a man.

Water Monitoring in the Pamunkey and Mattaponi Rivers

Dissolved oxygen and temperature levels in both the Pamunkey and Mattaponi Rivers are monitored daily (dependent on weather and river conditions) with HOBO U26-001 Data Loggers. Currently, loggers collect data at three positions (upper, middle, and lower) in the Pamunkey River and three positions in the Mattaponi River (upper, middle, and lower). The data are downloaded and posted by month as it becomes available. Additional data is collected at two points in the Pamunkey, to include salinity, pH, flow velocity, and turbidity from VIMS and USGS monitors.

The amount of gaseous oxygen dissolved in the water is a critical factor for assessing water quality. Low, or very high, levels, of dissolved oxygen negatively impact fish and other aquatic organisms. Water temperature affects the amount of dissolved oxygen in the water, as well as other biological aspects (i.e., metabolic rates of aquatic organisms) and chemical aspects (i.e., photosynthesis of aquatic plants). Dissolved oxygen and water temperature are primary stressors for the Atlantic Sturgeon.

Data links on the sidebar provide data collected in the Pamunkey and Mattaponi Rivers.

The Upper Pamunkey River logger was not deployed until October 2018 due to flooding. The Lower Mattaponi River logger required replacement and was positioned in a more secure location as of July 2019. Celsius to Fahrenheit conversion: (°C x 1.8) + 32 = °F

STURGEON SPECIES RECOVERY GRANT DATA

Pamunkey Water Data Archive 2020

Pamunkey Water Data Archive 2019

Pamunkey Water Data Archive 2018

Mattaponi Water Data Archive 2020

Mattaponi Water Data Archive 2019

Mattaponi Water Data Archive 2018

Cumulative Monitoring Data for Website Upload

PamunkeyVIMSEnviroData 1.1.18_11.1.20

PamunkeyUSGSEnviroData 1.1.18_11.1.20